SRI/ESG Primer

'Sustainable and Responsible Investment' has come a long way since the ethically-motivated boycotts of apartheid and the application of religiously-motivated ‘screens’.

From these principled roots, the industry has developed a diverse range of intellectually-mature and globally-applicable investment strategies - including an articulation as 'ESG' (Environmental, Social and Governance).

The pages below give a basic overview of SRI & ESG, describe the motivations behind these investment approaches, the strategies deployed and the terminology used.

It aims to answer all of the questions that newcomers to the industry may have. Also, its 'back to basics’ approach also throws up a few challenging concepts for those who think they know the industry inside out.

Over the years, many terms have been used interchangeably to describe the incorporation of ethical, environmental or social factors into investment fund management: ethical investment, socially-responsible investment, green investment, responsible investment, ESG - to name but a few.

The meaning of these various terms all overlap and many have particular resonance for different industry participants.

Sustainable (& Responsible) Investment

We prefer the term ‘Sustainable and Responsible Investment’ (SRI) meaning:

- ‘investment which takes sustainable development priorities into account’ or

- ‘investment which seeks to meet the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.

This latter definition aligns sustainable investment closely with the concept of sustainable development as defined by the Brundtland Commission in 1972.

ESG

The term 'ESG' is widely used and refers to the application of Environmental, Social and (corporate) Governance considerations to investment pratice.

Keep it practical

In such a fast-growing area, however, a broad-based term is best understood by reference to its current practical application rather than to any dictionary definition.

We describe some of the current practical applications on the following pages.

There are three fundamental motives for 'Sustainable and Responsible Investment':

- To avoid investor ‘complicity’ with activities that they object to

- To encourage / incentivise companies to improve their impact on society, the environment or the economy

- To generate investment outperformance

While the first of these provided the original motivation for SRI, the second two have become increasingly important in recent years and are now the primary motivation for many SRI investors.

Of course, a fourth motive drives investment institutions themselves: the motive of making money. Many investment institutions develop SRI / ESG capabilities to meet client demand – even if they do not share any of the fundamental motives outlined above.

More recently, regulators and disclosure regimes are requiring companies and investors to pay more attention to sustainability issues.

Different SRI strategies are selected to respond to each different motive – and each delivers a different outcome. However, some trace of each motive can be found in every strategy.

Over the past ten years, SRI has grown – across all styles and all geographies and at a rate that has outstripped growth in most other investment strategies. It has shown little regard for downturns in the wider market and has twice (tech-crash & credit crunch) paused for breath while other strategies have haemorrhaged funds.

This has belied the prejudice that SRI is a luxury for good times and the first thing on the chopping block when times get tough. Through both crashes, SRI has behaved as predicted in that existing SRI investors have proved to be stickier than others. It may even be that instability in other investment styles has attracted new investors to factors such as ‘responsibility’ and ‘sustainability’ as proxies for growth and security.

Establishing precise growth figures, however, is difficult due to a paucity of market data and the rapid development of styles which means that categories remain in a state of constant flux.

Valiant efforts size and categorise markets are made by the various Social Investment Fora – the results of which we summarise below.

Europe

The Eurosif European SRI Study 2010 reports that the total SRI assets under management (AuMs) have reached €5 trillion as of December 31, 2009. This is made up of €1.2 trillion of Core SRI and €3.8 trillion in Broad SRI. (Core SRI consists of elaborated screening strategies systematically impacting portfolio construction and often implying a values-based approach while Broad SRI partly represents the mainstreaming of SRI and the growing interest of responsible investors, particularly large institutional investors, in this area.)

USA

The Social Investment Forum’s 2010 Report on SRI Trends identified $3.07 trillion in total assets under management using one or more of the three core socially responsible investing strategies—screening, shareholder advocacy, and community investing. This equates to nearly $1 in every $8. The report also states that "Since 2005, SRI assets have increased more than 34 percent while the broader universe of professionally managed assets has increased only 3 percent. From the start of 2007 to the opening of 2010, a three-year period when broad market indices such as the S&P 500 declined and the broader universe of professionally managed assets increased less than 1 percent, assets involved in sustainable and socially responsible investing increased more than 13 percent."

Asia

ASRIA reports that total money under SRI management in Asia is less than US$2.5bn, but is likely to increase substantially as there are now over 200 funds in existence. Japan is the largest market with 50 funds.

Australia

The RIAA Benchmark Report notes that Core SRI in Australia totals $16bn while Broad SRI totals $60bn 2009. It notes that responsible investment in New Zealand total NZ$16bn.

Canada

The Social Investment Organisation’s Canadian Socially Responsible Investment Review 2010 reports that total Canadian assets invested according to socially responsible guidelines is $530.9 billion and that SRI is holding steady at about one-fifth of assets under management (AUM) in Canada.

Emerging markets

As far as we are aware, no formal market analysis has been published of the penetration of SRI within emerging markets.

As the ‘Sustainable and Responsible Investment’ industry has grown and evolved, its sophistication has increased greatly such that twenty-one distinct SRI strategies can now be identified:

- Ethical 'negative' screening – refers to the screening of companies on ethical, moral or religious grounds (such as contraception, lending at interest or animal testing).

- Shariah screening – is a sub-category of ethical screening which is guided by Islamic principles that lead to avoidance of activities that are ‘Haraam’ (forbidden) such as alcohol and pork or exposed to ‘Riba’ / usury (interest payment in the lending or accepting of money). (See Note 1 below)

- Environmental/social 'negative' screening – relates to the removal of companies or sectors from an investment universe for falling short of any absolute environmental, social or economic standards. (Such screening may remove companies exposed to activities such as nuclear power, pornography or tobacco manufacture.)

- Norms-based screening – is a sub-category of env/social negative screening which involves excluding from portfolios, companies (or government-debt) on account of any failure by the issuer to meet internationally accepted ‘norms’ such as the UN Global Compact, Kyoto Protocol, UN Declaration of Human Rights etc.)

- Positive screening – involves the active inclusion of companies within an investment universe because of the social or environmental benefits of their products and/or processes. (For example, all water companies may be included in a universe on account of the social benefits of clean water supply and the environmental benefits of wastewater treatment.)

- Best in Class – is a comparative investment style that involves investing only in companies that lead their peer groups in respect of environmental and social performance (under this approach, only a proportion of water companies may be included within an investment universe as only a proportion can be the ‘best’).

- Financially-Weighted Best in Class – is an investment style that incorporates financial (as well as economic, social and environmental) factors into the ‘best in class’ decision-making process – and gives weight to the sustainability aspects that are most likely to impact financial performance.

- Corporate governance (active) – involves the proactive execution of the general rights and responsibilities of share ownership. Practical execution typically involves (but is not limited to) the execution of voting policy.

- Constructive engagement – involves investors encouraging company management to improve the impact that they have on society and / or the environment through a process of research and dialogue

- Shareholder advocacy – is a more confrontational form of engagement, whereby investors use their shareholdings to submit resolutions to company AGMs and sometimes launch public campaigns against specific corporate practices.

- Sustainability theme investing – involves investment in companies exposed to industrial trends that arise from the pursuit of sustainable development (e.g. investment in renewable energy companies, water treatment companies, education providers etc).

- Alternative / renewable energy investment – is a sub-category of sustainability theme investing that involves targeted investment in renewable and alternative energy companies.

- Integrated analysis – fundamental approach – is an investment style in which fundamental analysis of environmental and social issues is used to adjust forecasts of key stock price drivers, to identify additional sources of risk and opportunity and, thereby, to contribute to better overall investment decision-making.

- Integrated analysis – quantitative approach – is an investment style that uses statistical methods to establish a predictive correlation between the sustainability aspects of a company’s performance and financial factors and to apply the resulting ratio to manage stock portfolios on a quantitative basis.

- Integrated analysis - for engagement – is a style in which the purpose of integrated sustainability analysis is to lend weight to a programme of engagement with the company owned – but where a buy/sell decision is not envisaged

- Community investing – involves the provision of capital and financial services to communities that are underserved by traditional financial services and particularly to low-income individuals, small businesses and community services such as child care, affordable housing, and healthcare

- Fonds solidaire (solidarity funds) – is a uniquely French strategy in which managers invest 5%-10% of their portfolio into unlisted companies that are officially accredited as meeting ‘solidarity’ criteria (by employing staff on supported job schemes, by sanctioning the election of management by the workforce or by applying certain rules on the pay of executives and staff)

- Economic empowerment investment – is a uniquely S. African form of SRI that involves direct investment in the economic infrastructure that is needed to support ordered and equitable economic growth together with sustainable community development

- Microfinance funds – are funds that invest in the equity of microfinance institutions that promote local economic development at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ through the issuance of ‘micro-loans’ and ‘micro-insurance’. (See Note 1 below)

- Income sharing funds – enable investors to donate a portion of their income to humanitarian or environmental causes

- Sustainable finance – is an investment style whereby specialist sustainability research enables capital to be allocated to companies and projects that lead directly to sustainable development – sustainability is the pre-eminent factor behind the investment decision. Investee companies or projects are typically unequivocally sustainable alternatives to mainstream businesses.

In addition to these, other terms that are used commonly – but do not classify as unique strategies - are:

- Impact investing – an umbrella term that groups a number of the styles described above (clean tech, microfinance, community investing etc.) through recognition of their role in delivering social and environmental benefits. It is often used as a contrast to styles that involve (positive or negative) screening of large cap stocks and is positions itself across a wide spectrum of financial outcome between philanthropy and mainstream investing

- ESG investing – a term that is used in some markets in place of ‘integrated analysis’ to refer to investment that uses environmental, social and governance factors to improve financial analysis –the term is typically used in contrast to contrast the strategy with screened investment

Note 1: Microfinance is also a component of Shariah investment

The SRI market continues to enjoy strong and steady growth. However within this, notable shifts are occurring in the strategies that are deployed:

- Screening – while there is little relative growth in ‘core basket’ (bombs, booze, baccy, bingo etc.) ethical screening, single issue screening (e.g. cluster bombs, Darfur) and norms-based screening (e.g. compliance with Global Compact) have gained traction in recent years

- Constructive engagement – is seeing strong growth in institutional markets and also resonates with retail investors. However, questions remain unanswered about the relative merits of ‘issue-focussed’ vs ‘company-focussed’ engagement, outsourcing and collaboration. We discuss these in our discussion paper: ‘Engagement: pause for thought’)

- Best-in-class –this strategy looks likely to retain its strength in continental Europe but (in spite of the author’s long-standing affection for it) cannot be classified as one of SRI fastest growing strategies.

- Integrated analysis – demand growth is strongest for products that support the integration of environmental and social considerations with financial analysis – partly because of the potential for financial outperformance and partly because this strategy underpins the investment logic of all other strategies. The emergence of this strategy is discussed at length in our discussion paper: ‘Integrated analysis: approaching a tipping point’

- Sustainability theme investing – saw strong growth through 2006 and 2007; although there was naturally some softening in some single theme strategies (e.g. renewable energy), this has been smoothed to some extent by a broadening of the thematic categories (to include new themes such as water theme, climate change, healthcare etc.)

Divergence with confidence

As strategies diverge and each develops its own growth drivers and momentum, asset managers are becoming more confident in pinning their colours to a selection of the strategies that have most synergies with their core asset management competence and fewer feel the need to offer one-stop-shops that cater to all SRI strategies.

Globalisation

The attention of asset managers is globalising. While the issues addressed are often, by definition, global, the growth of interest by institutional investors makes it easier to target a global client base and, as a result, their stock coverage has to expand to a global scope.

This is a gradual process and, in many cases, the starting point is modest – as in other areas of investment, some asset managers claim global coverage but, in reality, devote 70% of their attention to their domestic market; 20% to other markets in their region and 10% to the rest of the world.

Research sophistication

A number of factors combine to demand greater depth and sophistication in the sustainability research conducted (or commissioned) by asset managers. The most notable of these are: the greater sustainability sophistication of companies and the greater demand for research that integrates sustainability with financial factors.

Almost all SRI strategies are available in all major markets and most are attracting growing interest. However, there is considerable regional differentiation. The table below (which is based on anecdotal evidence) shows which strategies predominate in some different markets and which are growing faster than others.

Almost all SRI strategies are available in all major markets and most are attracting growing interest. However, there is considerable regional differentiation. The table below (which is based on anecdotal evidence) shows which strategies predominate in some different markets and which are growing faster than others.

| Negative screening | Best-in-class | Constructive engagement | Shareholder advocacy | Thematic investment | Integrated analysis | |

| USA | *** / o | x / o | * / o | ** / o | ** / + | x / o |

| UK | ** / - | * / - | ** / + | * / o | ** / + | ** / + |

| France | * / o | *** / o | * / + | x / o | * / + | ** / + |

| Netherlands | ** / + | ** / - | ** / + | ** / o | ** / o | ** / + |

| Switzerland | * / o | ** / - | * / o | x / o | *** / + | * / + |

| Scandinavia | ** / + | * / o | ** / + | ** / + | * / o | * / + |

Key

Degree of penetration of each strategy is indicated by:

***: One of the dominant strategies available in this market

**: A strategy deployed by a significant number of SRI managers in this market

*: A strategy deployed by a minority of SRI managers in this market

x: A strategy that is rarely applied in this market

Direction of travel is indicated by:

+: growing in usage (relative to other styles)

o: holding its own (relative to other styles)

-: diminishing in importance (relative to other styles)

(We plan to extend this over time to other markets, starting with Australia, South Africa, Japan, Germany, S.E.Asia etc. and would be interested in information that helps us to do this.)

As SRI has grown in size and sophistication, it has expanded to encompass more asset classes.

Equity

SRI was initially developed as an equity-focussed style of investment – and the vast majority of funds currently available are still invested in quoted equities.

Recently, SRI principles have been extended beyond quoted equities to incorporate:

- Venture Capital: through the growth of clean tech venture capital

- Private Equity: under the auspices of a work stream of the UN PRI that seeks to raise awareness and support implementation of SRI practices within this asset class

Bonds

Initially SRI strategies for bonds focussed on corporate bonds and deployed the same screening methodologies as are applied to equities. Recently more sophisticated techniques for screening governments and sovereign bond issues have been developed – initially by asset managers and then by SRI agencies.

At the same time issuers are experimenting with new bonds where the capital is hypothecated towards socially or environmentally beneficial projects – such as microfinance, vaccines or environmental / climate change projects. These bonds provide opportunity for positive screening funds.

Property

The impact of property on CO2 emissions and the potential social impact of property development has forms the basis for greater SRI activity by property investors. So far as we are aware, this interest has largely been channelled into making improvements to mainstream property investment processes and few discrete funds have been launched.

Cash

A number of SRI ‘cash’ funds have been launched – particularly in France. However, we have to confess that we struggle to understand the difference between an SRI cash fund and a non-SRI cash fund. We would be intrigued to hear from anyone who can explain it.

Commodities

The emergence of carbon markets (even though they are currently small and do not permit much diversification) have enabled some experimentation with sustainable commodities investment.

Other

Some investors are exploring how to apply SRI principles to the asset classes of forestry/timber and agriculture/land. In particular, they are exploring the synergies between these classes and their interest in climate change.

“Organic apples are a bit spotty; recycled paper jams the photocopier; SRI funds, like anything with worthy intent must underperform”.

- For years, conventional investment ‘wisdom’ has assumed that SRI funds will underperform their ‘mainstream’ counterparts. There is very little evidence that this is true.

“Investment strategies that align themselves with secular trends in the economy and society will outperform the wider market.”

- For years, SRI investors have argued that SRI funds can outperform their mainstream counterparts and that there is solid investment logic for this.

Although a growing body of academic research and fund performance data supports this latter argument (of SRI investors), many mainstream investors whose support will be needed to extend the uptake of SRI are still sceptical about SRI’s performance credentials.

The ‘proofs’ are outweighed by a number of misconceptions and prejudices. We address these on the following pages:

- Misconceptions and prejudices about SRI investment performance

- Proofs

The following all undermine, unjustifiably in our view, the argument that SRI can perform in-line with and even outperform conventional investment:

- SRI is all about ‘screening’

- Restricted universe => restricted performance

- SRI is primarily about achieving an ‘ethical return’

- There is an inherent conflict between ‘doing good’ and ‘doing well’

- SRI only looks to address downside risk

- A prejudice exaccerbated by using debt tools in a equity world

SRI is all about screening

Most objections to SRI performance emanate from the perception that SRI is confined to screening. As we highlight above, SRI now extends to 20 different strategies – all of which have different risk-return characteristics from each other. Some of these diverge substantially from their mainstream comparators, while others mirror precisely the investment characteristics of ‘conventional’ investment. For example:

- ‘Sustainable theme investing’ involves concentrated portfolios of typically smaller companies which (even if the trends that it tracks are secular, long-term market outperformers) may be considerably more volatile than the wider market.

- ‘Constructive engagement’, by contrast, merely seeks to exert influence upon companies that are already held within a fund; the SRI element of the process does not generate ‘buy’ or ‘sell’ instructions and the strategy, therefore, has no investment impact at all*.

- ‘Ethical / negative’ screening fund performance will naturally suffer / benefit from the performance of sectors that are excluded (unless, as is often the case, this exposure is hedged in other ways); where exclusions are few, performance is likely to be in line with the market; where they are numerous, performance can deviate substantially

- ‘Integrated analysis’ – aims to generate investable ideas from the analysis of environmental and social information. However, as these ideas are processed through the same analysis and selection process as all other investment ideas, these will only affect the portfolios performance if their merits (as judged by the portfolio manager) outweigh those of more conventionally-generated investment ideas

(* Some contend that the purpose of constructive engagement is to improve the business (and thence investment) performance of companies held. There is merit in this argument, but outside major activist corporate governance interventions, practical evidence is rare.)

Restricted universe => restricted performance

Received investment ‘wisdom’ often argues that restricting an investment universe increases risk and reduces opportunities for performance. The counter arguments which are that:

- SRI funds invest into fundamental secular trends towards higher standards of environmental and social sustainability and will outperform as these trends develop

- Strong environmental and social performance are indicators of high quality management – and may therefore be lead indicators of investment performance

- Reductions in universe size enhance a fund manager’s focus on the stocks that he/she can hold

- All fund managers effectively operate to a restricted list. While the restrictions of SRI fund managers are formalised, their ‘mainstream’ counterparts are restricted by the fact that their brains can only focus on a given number of companies at any one time

- Restrictions in an investment universe imposed by sustainability considerations can be compensated for in other areas – a manager of a global SRI fund has many more stock opportunities than a manager of an ‘unrestricted’ UK fund)

SRI is primarily about achieving an ‘ethical return’

Although the ‘ethical return’ is what distinguishes SRI funds from their mainstream counterparts, this does not necessarily (or even often) make it the dominant factor within these funds.

Outperforming the market is as important to SRI fund managers as it is to conventional fund managers. Whilst there may be some retail investors who would trade financial return for a higher ethical return, there are very few fund managers who will give them this opportunity.

SRI managers will typically argue that investment performance is their dominant priority and will contest (as below) the suggestion that there need be a conflict between this and sustainability performance.

There is an inherent conflict between ‘doing good’ and ‘doing well’

Not necessarily! Sometimes there is a conflict between ‘doing good’ and ‘doing well’; sometimes there is a synergy between the two. The context within which a company or investor operates is critical.

Proponents of SRI will, of course, argue that as the scientific, political, economic and civil case for sustainable development builds, the legislative, regulatory and customer context is ever more likely to reward companies and investors that do good. Furthermore, as more investors become aware of this, premium

Even where this is not the case, it must be noted that an active manager of SRI funds can exploit the synergies where he/she can identify them– but is not bound to ‘do good’ if it would compromise the fund’s investment performance.

SRI only looks to avoid downside risk

Environmentalists are often regarded as miserable Cassandras who focus only on what can go wrong. However, it is a mistake to assume that just because environmental scientists paint a gloomy picture of the future, environmental investment analysts are exclusively focussed on avoiding downside risk.

Smart analysts should recognise that ‘sustainable development’ is simply a process of change and that pro-active companies should be able to adapt faster to changing circumstances and perceptions than consumers, politicians and their peers – such that they benefit from changed patterns of behaviour, regulation and purchasing and financially outperform their peers in the process.

Although SRI analysts should focus as much on identifying opportunities and share price upside as they should on evaluating and avoiding downside risk, it has to be acknowledged that the SRI industry has not always helped itself in three respects:

- SRI investors can be too ready to slip back into the language of ‘risk avoidance’ rather than that of ‘opportunity capture’ when discussing sustainability and investment

- When they do talk about upside potential they are too quick to select their examples from the obvious sectors of alternative/renewable energy, water treatment and waste management instead of selecting less obvious (and therefore more compelling) examples from sectors such as food retail, autos, chemicals, mining etc.

- Finally, the SRI industry focus on ratings which are really ‘debt market’ tools that have been artificially imposed on equity markets reinforce prejudices about ‘downside risk’

Debt tools in an equity world

‘Ratings’ are used in debt markets, to indicate the likelihood of default. They grade the possibility of a fundamentally binary outcome (‘default’ or ‘no default’) where the outcome is neutral or negative.

Equity markets, by contrast, need to consider upside-potential as well as downside-risk. They also need to evaluate the quantum of that upside or downside in closer detail. Although equity recommendations are often grouped into BUY/HOLD/SELL or OUTPERFORM/UNDERPERFORM categories, these are merely broad indicators of much more specific target prices.

The use of ‘ratings’ in SRI can therefore serve to perpetuate a prejudice among equity investors that environmental and social issues are predominantly about avoiding downside risk.

Three avenues are being explored to counter these prejudices and ‘prove’ that sustainability factors add value to the investment process:

- A top-down / quantitative approach

- A bottom-up / fundamental approach

- Fund performance

(These are also the two different approaches to ‘integrated analysis’)

Quantitative ‘proofs’ – fighting fire with penicillin

Numerous academic studies have been conducted into the performance of SRI funds relative to their conventional peers. Notable studies are listed at SRI Studies with the best each year being awarded the Moskowitz prize. Most recently the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) commissioned Mercer to produce a study on Demystifying Responsible Investment Performance.

While the inputs for the studies vary, they typically seek quantitative correlation between sustainability inputs (datapoints or ratings) and financial effects (investment ratios or stock performance).

The Mercer study reviewed 20 academic studies and categorised them according to whether the sustainability effect was found to have a positive, neutral or negative effect on investment performance. 10 of the studies found the effect to be positive, 7 neutral and 3 negative. This ratio is broadly in line with similar SRI studies over a long period of time: that any SRI effect is either positive or neutral/non-existent. Put another way, sustainability investment either outperforms or, at worst, performs in line with conventional investment.

However, these quantitative ‘proofs’ have made little headway in convincing mainstream investment practitioners – largely because the research has been conducted on terms that do not resonate with the audience that they are trying to convince:

- They seek academic ‘proofs’ not investable ‘ideas’

- They look backwards at what has happened – not forwards to what may happen

- They use ‘top-down’ techniques - not the bottom-up fundamental ones that are valued by the investment managers that the ‘proofs’ aim to convince

- These are targeted at a minority investment style – quantitative fund management

- None of the studies consider whether any ‘sustainability effect’ is ‘already in the price’ – and give no purchase for investigating further

- They seek correlation only – not causality

More significantly, however, the industry is relying on intricate, quantitative and academically-rigorous studies to tackle gut-based prejudices. SRI analysts are, perhaps, overcompensating for their non-financial background by reaching for the most intricate and quantitative methods available. It is like using penicillin to fight fire.

Fundamental (bottom-up) ‘proofs’

The ‘fundamental’ approach, by contrast, aims to prove the performance pudding through the eating – that is to say, it aims to generate a stream of investment ideas (that are material, actionable, timely and effectively communicated) and to apply these to the process of stock selection.

This approach will never produce neat, generally-applicable, easily-presentable ‘proofs’ (so is of little use to the media or to conference presenters). Indeed, it does not aim to. Instead of ‘proving’ an abstract case about SRI performance, the bottom-up approach looks to convince mainstream investor clients, colleagues and companies that it can generate investment outperformance in exactly the same way and on exactly the same terms as all other investment approaches – by identifying anomalies in valuation and generating investment ideas.

This approach integrates much more closely with other techniques for generating investment outperformance and is therefore more convincing to investment colleagues, to clients and to companies. It is also gets closer to the capabilities of SRI analysts and to the issues faced by companies.

At present the only measure we have of this approach is the anecdotal evidence that SRI analysts are presenting a greater number of investable ideas to their mainstream colleagues and seeing a greater uptake of them and that more explicit sustainability elements are featuring in broker recommendations. We do not, however, yet have evidence on how these ideas and recommendations have performed.

Fund performance

Of course, the ultimate test of SRI’s ability to outperform comes from the performance of SRI funds. Where such analysis has been undertaken, it has tended to support a ‘perform-in-line’ / ‘marginal outperform’ conclusion. However, in the absence of any comprehensive global study that controls for variations in fund domicile, investment style, benchmark index, fund sector, SRI strategy etc. we would prefer to leave the market to be the best judge of this.

Over the past twenty years, SRI practitioners have continuously developed and updated the range of SRI strategies and investment applications such that the industry can now offer products that cater for all investor types with all levels of risk appetite and vehicle preference.

Investment styles

SRI strategies are applied to a range of different investment styles including:

- Active management - Most SRI funds are actively-managed and are based on the premise that sustainability analysis is one factor that can enhance the performance of an active fund manager

- Passive management – funds that track all of the major SRI indices – both screened and thematic – are widely available

- Quantitative management – in spite of the exertions of ratings agencies to promote the concept (and in spite of its extensive discussion in academic research and in the media) very few SRI funds are managed on a quants-basis

(Governance and engagement-based strategies can, of course, be incorporated into all of the above investment styles)

Investment vehicles

The best known SRI funds are those which are offered to retail investors through open-ended mutual funds. However, SRI strategies can be deployed within almost all investment vehicles:

- Most institutions will run discretionary SRI portfolios for institutional investors

- There are a few closed-ended funds – mainly in the environmental technology area

- ETFs – are available to track both screened indices and thematic ones and are growing in popularity

- Some SRI hedge funds are available – so far as we are aware, most of these use long-short equity strategies and avoid high-levels of leverage

- There are a number of SRI funds of funds and even an SRI hedge fund of funds

Customer segments

The range of products and strategies detailed above now give SRI the flexibility to provide for most investor types including:

- Individuals

- Individual (retail) investors

- High-net worth investors

- Institutions

- Pension funds (for employees from the:

- Private sector

- Public sector

- Third sector

- Insurance funds

- Sovereign wealth funds

- Churches, charities and foundations

- Pension funds (for employees from the:

This diversity of customer base has the additional advantage of smoothing growth in the overall industry as attention tends to fall on different asset owners at different times.

In a fast-developing field, action is more important than terminology. Nonetheless, clarity of description is important to ensure that thought defines language rather than the other way round. So here are a few thoughts on terms that are common in the SRI industry.

Sustainable Development

‘Sustainable development’ (or ‘sustainability’ for short) was elegantly defined in 1972 by the Bruntland Commission as “development that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

Although not all SRI funds subscribe to the concept of ‘sustainable development’ (most do) and the concept certainly lacks the practical detail; it is, nonetheless, a useful touchstone for all SRI investors and for those engaging with this industry.

ESG (environmental, social and governance)

The term ‘ESG’ is ugly and misleading but, unfortunately, becoming more widely used. It is misleading because it conflates two structurally different dimensions of corporate activity and ignores one. It conflates sustainability issues and corporate governance issues and it ignores the economic dimension of sustainability.

Investors will typically be interested in how companies manage all of the factors that contribute to the profitability of the company: production, marketing, product development, employees, regulatory relationships etc. In addition to this, SRI investors will have particular interests in those factors with social, environmental or economic dimensions.

On top of these issues and management processes, investors will expect companies to have a structured system of corporate governance to balance the interests of management and shareholders and to ensure that the latter are properly informed and their interests appropriately represented in major decision-making.

Although all three are needed, the ‘corporate governance’ system is structurally different from the management system that it overlays and the issues managed by that system.

The dimension that’s missed is the economic one. Sustainability investors are generally concerned with the relationship between economic, social and environmental factors and the financial performance of companies. Although it corrupts the phrase, this is a ‘quadruple bottom-line’.

It is instructive to note that the term ‘ESG’ did not arise from any research framework or theoretical assessment but out of the practical need of investment managers to resource two areas of research and engagement that extended beyond their conventional boundaries and to communicate their activity to clients. A virtue was made of this necessity by a number of houses and it has been used to extend the influence of both ‘corporate governance’ and ‘sustainability research’.

The term has done no harm and may have hastened the uptake of sustainability in a number of areas. However, caveat, it is jargon; it is inaccurate; it is not a good basis for rigorous and comprehensive research.

Corporate Social Responsibility / Corporate Responsibility

Bearable! Just! But desperately limited in its ambition – ‘CSR’ or ‘CR’ says “we need to be as responsible as society currently expects us to be”. By contrast, “Sustainability” says “we need to align ourselves with the major social, environmental and economic changes that face society at large – and prepare ourselves for the world that will be”.

Ethical investment

Although SRI was originally known as ‘ethical investment’, it now deals with so few issues that can be accurately described as ‘ethical’ (as opposed to ‘social’ or ‘environmental’) that the term no longer has much currency outside its (often strong) marketing benefits in some retail markets.

Extra-financial

Now this one would make an interesting case study for a student of linguistics – a word invented by one group (the Enhanced Analytics Initiative) for one specific time and purpose – but with probably no long-lasting meaning.

The term ‘extra-financial’ was specially coined to motivate a given audience (sell-side brokers) to think outside their usual parameters (the financial) without prejudging the issues that they would decide to focus on.

The reports of the Enhanced Analytics Initiative catalogue the success of this and the limitations – and need no additional commentary from me.

Will the term last? Probably not – but it was probably never intended to – it served its purpose. After all, the term is defined by what it is not!

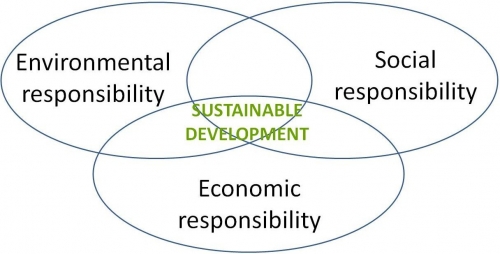

‘Sustainable development’ (‘sustainability’ for short) was well-defined in 1972 by the Bruntland Commission as “development that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

The 'triple bottom line'

It was usefully made applicable for the business community by the phase the ‘Triple Bottom Line’ and the Venn diagram that shows the need to balance environmental, social and economic factors.

However, further consideration reveals that this three-way balance still falls short of describing what companies need to do.

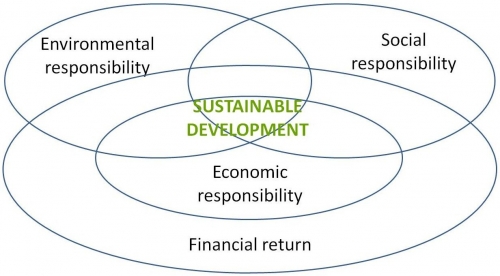

The 'quadruple bottom line'

Companies need to make four returns, to the environment, to society, to the economy AND, a financial return, to shareholders. This is a quadruple bottom line. For too long, companies and investors have conflated the meaning of ‘economic’ and ‘financial’ returns.

The ‘financial’ return is the return that companies make to shareholders in terms of capital growth and dividends (this is well understood)

The ‘economic’ return, by contrast, is the return that a company makes to the (national or local) economy in terms of its promotion of economic growth, stability, productivity and competitiveness in the markets within which they operate. (this is rarely effectively understood or reported)

Consider the question over the expansion of airports – the debate is between the level of economic benefit that larger airports bring (or don’t) with the level of environmental damage that they cause. The financial benefit to the airlines or the airport operators is a separate question.

If a further example is needed, consider the recent failure of the banking system. For years, banks had focussed on the returns to shareholders (their financial responsibilities) but had forgotten their wider economic responsibilities (to support a functioning economy). The subsequent government intervention is a (belated) recognition that the banks failed to manage the fourth bottom line. Interestingly, SRI investors that do not separate this fourth (economic) bottom line from the first (financial) one would have missed the banking collapse and will miss the next one.

The 'quintuple bottom line'

Finally, companies are obliged to operate within an ethical or moral framework which is likely to be defined by the religious and non-religious beliefs of their wider community – but may have no direct relationship to other social, environmental, economic or financial considerations.

This adds up to a five-way balancing act for companies - a quintuple bottom line!

Or even six?

Some SRI analysts will insist that a companies' corporate governance obligations be placed on a level with their environmental and social obligations (using the phrase 'ESG'). We tend to draw the line at five and argue that corporate governance deals with the management and reporting process rather being something that is to be reported upon.

Further information on the SRI industry and its dynamics can be found from:

Social investment fora

The original and leading suppliers of SRI industry information and market data are the Social Investment Fora of different countries and regions.

Industry commentators

Apart from the Social Investment Fora, there are a few specialist providers of SRI news and comment. Of these, the following deserve particular note:

- Environmental Finance (http://www.environmental-finance.com/)- a monthly magazine covering the ever-increasing impact of environmental issues on the lending, insurance

- Novethic (http://www.novethic.com) – a research centre that tracks developments in the French market

- Responsible Investor (http://www.responsible-investor.com/) – an online publication that tracks developments in the SRI market around the world and interviews participants in the industry